By

Opher Ganel, Ph.D.

Opher Ganel is an accomplished scientist (particle physics), instrument designer, systems engineer, instrument manager, and professional writer with over 30 years of experience in cutting-edge science and technology in collider experiments, sub-orbital projects, and satellite projects.

Learn about our Editorial Policy.

To make Wealthtender free for readers, we earn money from advertisers, including financial professionals and firms that pay to be featured. This creates a conflict of interest when we favor their promotion over others. Read our editorial policy and terms of service to learn more. Wealthtender is not a client of these financial services providers.

➡️ Find a Local Advisor | 🎯 Find a Specialist Advisor

It’s my favorite quote.

Not least of which because it’s often misattributed to Yogi Berra, which makes me smile.

“It’s hard to make accurate predictions, especially about the future.” – Nils Bohr, Danish physicist and 1922 Nobel laureate

Experts Rush in Where Angels Fear to Tread

Paraphrasing the well-known proverb, it seems investment experts keep making market forecasts, despite Bohr’s above-mentioned admonition.

But maybe they’re just that good.

Or are they?

In a short and highly readable post, “Be skeptical of stock market predictions for the coming year,” Mark Hackett, CFA, CMT, claims they aren’t, and backs it up with data.

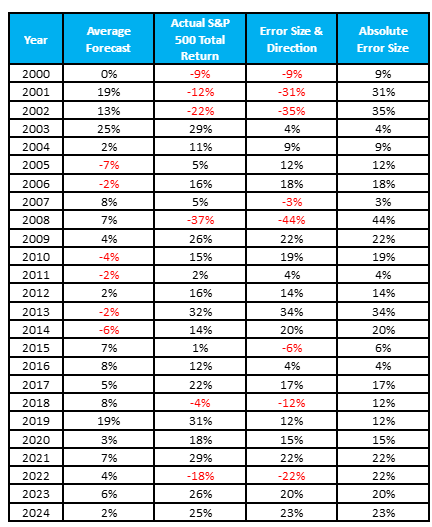

The following table shows Hackett’s average forecast data, actual annual S&P 500 total returns from SlickCharts, and their differences and absolute differences (e.g., a negative 5% error is an absolute error of 5%).

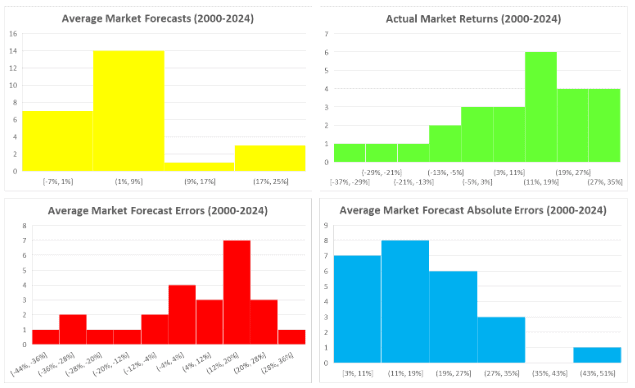

In graphic form, here are histograms of the forecasted returns (yellow, top left), actual returns (green, top right), errors (red, bottom left), and absolute errors (blue, bottom right), respectively.

In the above, a negative error means the experts overestimated the actual return while a positive error means they underestimated it. An error of 0, had there been any such, would have meant they hit the nail on the head.

As we see:

- The most prevalent range of forecasts was 1% to 9% (see the yellow plot, top left); whereas the most prevalent actual returns were in the 11% to 19% range (green plot, top right).

- In 25 years, forecasts hit within 3% of the actual returns once, 4 times managed to get within 5%, and were off by less than 10% seven times, meaning they were off by double digits over 70% of the time.

- The most prevalent error was in the 11% to 20% range (red plot, bottom left); the average absolute error was 17%, with the most prevalent value in the 11% to 19% range (blue plot, bottom right).

- Twenty-five years’ worth of forecasts ranged from -7% to 25%, a 32%-wide range; compare this to the actual returns that ranged from -37% to 32%, a 69%-wide range (more than double the width of the forecasts’ range); forecasts called for 5× smaller worst-case losses and 1.3× smaller best-case gains than ended up occurring.

- Forecasters hit the number of down years dead on, at 6 out of 25 years; however, none of the 6 forecasted down years saw an actual market decline (the average return for those 6 years was a 14% gain!), and the forecasts for the 6 years the market ended losing ground all called for gains (forecasting an average 8.5% gain for those 6 years of actual declines).

- None of the 25 annual forecasts called for a correction (10% decline) much less a bear market (20% decline), which meant the forecasts missed 2 corrections and 2 bear markets; in fact, the average forecast for the 4 “significant down” years called for a double-digit gain.

- They underestimated the actual return more than 2 times out of 3 (i.e., they were more likely to have made an overly conservative forecast than an overly aggressive one); a plausible explanation might be that people are less likely to be upset if their returns were higher than predicted rather than lower, let alone an unexpected loss).

What Do the Experts Forecast Now?

Given the questionable track record in forecasting annual returns seen above, it’s perhaps better to look at intermediate-term forecasts, i.e., 7-10 years out.

According to Morningstar’s Christine Benz, “In their most recent release, nearly every firm in my roundup had reduced their return expectations for US stocks. Meanwhile, every firm in my survey is expecting higher returns from non-US stocks than domestic over the next 10 years, and some firms’ 10-year bond market forecasts are higher than their return expectations for US stocks.”

She then continues to say, “The firms… all prepare capital markets forecasts for the next seven to 10 years, not the next 30… As such, these forecasts will have the most relevance for investors whose time horizons are in that ballpark, or for new retirees who face sequence-of-return risk in the next decade.”

With this in mind, let’s look at the forecasts for the coming decade across six firms.

- US equity forecasts call for gains ranging from 2.8% to 6.7%.

- Developed market equity forecasts call for gains ranging from 7.1% to 9.6%.

- Emerging market equity forecasts call for gains ranging from 5.2% to 11.0%.

- US aggregate bond forecasts call for gains ranging from 3.7% to 5.3%.

Three things stick out to me.

- None of the asset class forecasts call for a negative average return in the coming decade.

- Foreign markets are expected to outperform US equities by a significant margin, which makes sense given the 8-year average US outperformance since 1975 vs. the current outperformance cycle that’s already 14 years long.

- Bond performance forecasts have a tighter range than equity forecasts, and their mid-ranges are almost identical (4.5% vs. 4.8%), so equity investors may be taking more risk per unit expected return in the coming decade than bond investors.

My Observations and Takeaways from All the Above

The father of value investing, Ben Graham once said, “In the short run, the stock market is a voting machine. But in the long run, it is a weighing machine.”

As relates to forecasts, making accurate short-term forecasts is made well-nigh impossible by the multitude of short-term influences the market experiences.

Wars, weather catastrophes, pandemics, recessions, inflation, changing monetary policies, changing trade policies, etc. can each push down or pull up the overall market, specific industries, and far more so individual companies’ stock prices, as investors vote with their wallets as to which investment to pile into and which to shun.

However, over the long term, these all end up as noise that causes mere short-term deviations from the market’s very long-term average inflation-adjusted annual gain (about 7% for US stocks).

With all this in mind, here are my personal observations and takeaways.

- In the modern era (the 80 years since the end of World War II), the US stock market has had 18 down years (fewer than 1 in 4), 4 corrections (1 in 20), and 3 bear markets (less than 1 in 25). This is why I kept our stock market allocations at an aggressive 90%, even when conventional wisdom would have recommended a more age-appropriate 60% to 70%. If I had a decade or more until we needed to start drawing down our portfolio, I’d stick with a portfolio heavily tilted to stocks, with a larger-than-usual emphasis on international stocks. This is because while forecasts for the coming year don’t seem to get even the direction of market performance right, intermediate- and long-term forecasts are less inaccurate.

- Having said all that, reversion to the mean is a thing – when the market outperforms “too much for too long,” it will at some point start underperforming such that over “long enough” periods, it will return to its average (or mean) performance. Similarly, if returns are “too low for too long,” at some point, the market will outperform. From 2000 to 2024, the US market returned an annualized nominal average of 7.7% and an inflation-adjusted, or “real” return of 5.0% – both lower than the market’s long-term averages. Looking at 2005 to 2024, these numbers were both higher, at 10.3% and 7.5% – closer to the long-term average for the market – demonstrating an upward reversion to the mean. However, looking at the 16 years since 2009 (i.e., mostly after the so-called “Great Recession”), the market showed a nominal 14.6% gain and a real return of 11.7%! Given how much higher than average these numbers are, it would be reasonable to expect underperformance to hit the market at some point. However, it’s impossible to predict if that will happen this year, next year, or a decade from now (I’d bet a nickel it won’t be quite that long). I would not be shocked if this sort of thinking played a part in the current set of intermediate-term forecasts.

- One can similarly look at more specific asset classes, e.g., mega-cap growth vs. small-cap value, tech vs. other sectors, etc. When I look at the recent runup in mega-cap growth stocks, especially tech, and most especially the so-called “magnificent seven” – Amazon, Alphabet (a.k.a., Google), Apple, Meta (a.k.a., Facebook), Microsoft, Nvidia, and Tesla – all of which have dramatically outperformed from 2022 to 2024, it would be plausible to expect them to start underperforming at some point (at least relative to their recent sprint). And indeed, according to Investopedia, all seven are now in negative territory year-to-date (as of March 19), having lost up to half their value since 2025 began.

- Since I plan to start drawing money from our portfolio in 2-3 years, I’m much more concerned with the sequence-of-returns risk that could force me to sell more shares when the market is down, depleting our nest egg faster than we can afford. Mitigating this risk requires a much more conservative approach than I’ve kept during our accumulation phase. Thus, I’m increasing our bond and cash-equivalent allocations. Similarly, I’m changing our allocations to be more balanced than growth and avoiding overweighting mega-caps and/or tech stocks, since those sub-classes seem most ripe for a negative reversion to the mean. If the experts’ forecast for the coming 7-10 years is at least directionally correct, I won’t be giving up as much return as I would in more “normal” times for the US stock market.

- Once I set our allocations to suit our situation vis-à-vis our time horizon, I’ll try to avoid making changes based on expert forecasts (but hey, I’m as human as the next guy, so I probably won’t do this perfectly).

Ronald Lang, Principal & Chief Investment Officer for Atlas Wealth Management agrees, “When it comes to market forecasts, they’re nice for conversation, but you should not invest, trade or plan your portfolio allocation based on them. There are many smart market strategists who have data above and beyond what the average investor has access to, and they still don’t know. We like to read how those market strategists try to justify their forecasts when they are posted by early December to prepare for the upcoming year.

“I find it beyond comical that we’ve already had a couple of strategists who adjusted their 2025 year-end targets by mid-March. When they came up with their targets in December 2024, they already knew the election results and included the possibilities in their models for a forecast in the upcoming year. That doesn’t make much sense to me or the average investor because they (should have) considered the anticipated uncertainty with tariffs and geopolitical events. One thing is for sure, most forecasters will probably update their year-end targets again before the end of the year. Again, it can be a good conversation starter but should not be considered actionable.”

The Bottom Line

Another quote I’m fond of comes from Jewish sage Rabbi Yochanan (30 BCE to 90 CE) as written in the “Gmara” that says (my unofficial translation), “Since the destruction of the [Jewish] temple, prophesy has been taken from the prophets and given to fools and infants.”

Once more, the message is that knowing in advance what will happen, in general, let alone when looking at something as volatile as short-term stock market returns is impossible.

In short, nobody has a functioning crystal ball.

Knowing this, even so-called expert forecasts should be taken with more than a grain of salt.

The best way I think these forecasts can be used is to average a large number of independent forecasts, and even then, expect them to be at best directionally accurate over 7-10 years (but not over any single year, let alone shorter periods).

On top of this, I’d view such averages as interesting information, but would stick with whatever my financial plan says is appropriate given my goals (comfortable retirement), risk tolerance (higher than average for my age), and investing horizon (shorter now than previously).

As Benjamin Simerly, CFP®, Financial Advisor and Owner, Lakehouse Family Wealth says, “Hands down, the most common question I get is, ‘So, where do you think the market is headed?’ Predicting the future is an age-old tale. In fact, there’s an argument to be made that it’s second only to the world’s oldest profession… We advise clients that market predictions are a great way to lose focus, and discussions on economics and financial and tax planning are a great way to better your retirement. At the end of the day, bringing the focus back to the long-term retirement plan is the best way to spend time as it relates to investments. If a client’s investments align with their long-term plan, then that’s usually where they should stay.

“But what about the other form of prediction; market commentary? There are those in the industry who appreciate healthy economic discussions and learning, and this is where we focus our reading at Lakehouse Family Wealth. My favorite is the weekly newsletter sent out by Brian Wesbury, Chief Economist at First Trust. Not only does he take a healthy and moderate approach to his discussions, but it’s from the standpoint of a perpetual student, not a guru. The difference between the two is key: predictions are almost always wrong, according to both the data and common sense, whereas ongoing learning almost always benefits long-term goals.”

Does all this mean you should do the same as I plan to do?

Possibly.

However, my recommendation would be to work with a trusted financial planner to figure out what approach best fits you and your situation.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only, and should not be considered financial advice. You should consult a financial professional before making any major financial decisions.

About the Author

Opher Ganel, Ph.D.

My career has had many unpredictable twists and turns. A MSc in theoretical physics, PhD in experimental high-energy physics, postdoc in particle detector R&D, research position in experimental cosmic-ray physics (including a couple of visits to Antarctica), a brief stint at a small engineering services company supporting NASA, followed by starting my own small consulting practice supporting NASA projects and programs. Along the way, I started other micro businesses and helped my wife start and grow her own Marriage and Family Therapy practice. Now, I use all these experiences to also offer financial strategy services to help independent professionals achieve their personal and business finance goals. Connect with me on my own site: OpherGanel.com and/or follow my Medium publication: medium.com/financial-strategy/.

To make Wealthtender free for readers, we earn money from advertisers, including financial professionals and firms that pay to be featured. This creates a conflict of interest when we favor their promotion over others. Read our editorial policy and terms of service to learn more. Wealthtender is not a client of these financial services providers.

➡️ Find a Local Advisor | 🎯 Find a Specialist Advisor